Vice-chancellors are sticking around for longer – and, on average, they stay put for more years than any Secretary of State for Education ever.

We recently supported the Higher Education Policy Institute to published a new paper on the changing tenure of UK university vice-chancellors over the past half a century.

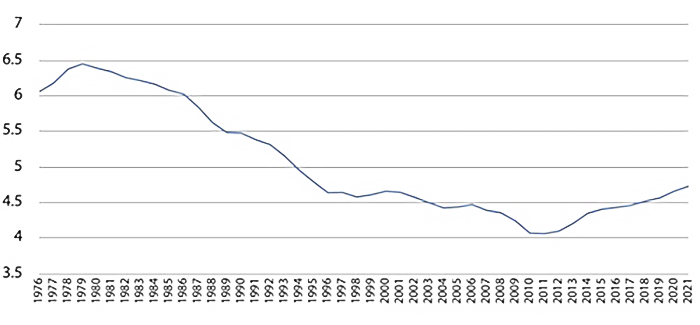

Digging in? The changing tenure of UK vice-chancellors (HEPI Policy Note 34) shows that, from the late 1970s to 2011, the average tenure of in-post vice-chancellors declined significantly – from 6.4 years to 4.1 years, a drop of 36 percent.

However, since ‘marketisation’ received rocket boosters in the Coalition years, with – for example – a big increase in tuition fees and the liberalisation of student places in England, the average tenure of UK vice-chancellors has increased. For serving vice-chancellors, it is now approaching 5 years (and is up around 15% from its lowest point a decade beforehand). This is the highest it has been since the turn of the millennium. Back in 2010, just one vice-chancellor (2 per cent of our sample) had a current tenure of 10 or more years; in 2021, eight did (16 percent).

By the time vice-chancellors stand down, they have on average spent eight years in the job, way above other professions to which they are sometimes compared. For example, the average tenure of a Premier League football manager is two years and one month and the average tenure of a senior NHS executive is around three years.

The tenure of vice-chancellors is also very much longer than senior Government Ministers, who tend to hold their posts for around two years. No top-level government minister with responsibility for education has ever matched the eight-year tenure of the average retiring vice-chancellor – the closest was Sir John Eldon Gorst, who was Vice-President of the Committee of the Council on Education for just over seven years between 1895 and 1902.

- England has had twelve different Secretaries of State for Education (though the post has sometimes had different names) since New Labour came to office in 1997.

- Scotland has had 10 incumbents in the comparable post since devolution in 1999 and Wales has had eight, while Northern Ireland has had five (as well as periods of direct rule during which five London-based Ministers have been in charge).

The paper claims no university could have coped smoothly with so many leadership changes in such a small space of time. Indeed, any institution with so many changes at the top would surely be widely regarded as failing.

Nick Hillman, Director of HEPI and the author of the report, said:

A few years gap, the best guess was that the enormous pressures on vice-chancellors would make it a less appealing role, despite the typically high renumeration. Then came Brexit, COVID and high inflation – not to mention industrial action – all of which might also have been expected to encourage some vice-chancellors to give up their roles more quickly.

However, our illuminating new research shows the opposite is true. University leaders have been staying in post for longer. It seems many vice-chancellors feel a strong obligation to see their institutions through turbulent times and their governing bodies have supported them to do so.

Nonetheless, it is far from inevitable that the current trend will continue as the university sector faces growing funding pressures, continuing industrial relations issues and more fallout from the so-called “culture war”.’

Julia Roberts, Practice Lead Education at GatenbySanderson, said:

HEPI has provided some very interesting insights on vice-chancellor tenures. We know from our very many conversations with higher education leaders that the last few years have been incredibly challenging for vice-chancellors personally and for their institutions.

This data bring to life the importance for everyone involved in recruiting higher education leaders to identify and support the next generation of vice-chancellors and secure the much needed diversity in top teams to face what’s ahead.’

Professor David Latchman CBE, who has led Birkbeck, University of London since 2003 and is the longest serving institutional leader included in the study, said:

Throughout the numerous crises of my almost 20 years at Birkbeck, I have found it valuable to stand in our lobby just before 6pm and watch our students pour in from work clutching their coffee cups and eager to learn. It stimulates me to continue to try and do my very best for them and confirms what a great job I have.’

Methodology

We have calculated the tenure of vice-chancellors in four different ways: i) the annual average for current vice-chancellors; ii) the 10-year rolling average for current vice-chancellors; iii) the annual average for departing vice-chancellors; and iv) the 10-year rolling average for departing vice-chancellors. As we are working with a time series, we only include older UK institutions, numbering 51 in total. We exclude Oxford and Cambridge because of their past practice of short-term rolling vice-chancellors. Each period of leadership is included separately even if the same person has led more than one institution. Further details are included in the Policy Note, including (in the Annex) a full list of institutions covered by the research.